The Supreme Court wrapped up its 2013-2014 session by releasing a decision determining when, exactly, the Senate is in session. For supporters of a strong Legislative Branch, its decision in the case of National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning was praiseworthy in some respects—but the majority opinion was worrying in others. It limited the President’s overreach in this case, but still allows future Presidents to grow their power at Congress’ expense.

In early January 2012, President Barack Obama invoked his constitutional authority to make recess appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). One business, Noel Canning, objected to an NLRB decision on the grounds that the Board lacked the necessary quorum to do business, since, they claimed, the recess appointments were invalid. They argued that the Senate was not in recess when the appointments were made, since the body was holding pro forma sessions, which last only a few minutes and generally see no business concluded. The Ad ministration argued that the pro forma sessions were mere technicalities and did not in any way impede his constitutional prerogatives.

To its credit, the Court ruled unanimously that the appointments were invalid. However, the Court was divided 5-4 on the reason for the decision. The majority and the concurring justices diverged on a couple principle questions:

- May the President only invoke the Recess Appointments Clause after the Congress has adjourned for the last time of the year, commencing a period known as the inter-session recess? Or may he also use the power during other breaks, known as intra-session recesses?

- And may the President fill only those vacancies that come open during the recess? Or may he fill those that pre-existed and continue during the recess as well?

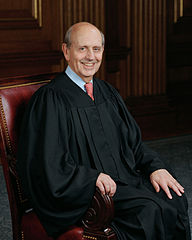

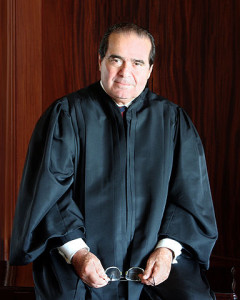

Although the whole Court thought the appointments were unconstitutional, the majority and the concurring justices ruled exactly the opposite on each of these questions. Justice Stephen Breyer, writing for the majority, wrote that the President could fill any vacancy during any substantial recess, whereas Justice Antonin Scalia, for the concurring justices, wrote that the President could only fill positions that came open during inter-session recesses.

It should be noted that prior to the Obama Administration, although this is the first time the Supreme Court has ruled on the Recess Appointments Clause, Justice Breyer’s viewpoint was the one commonly held by modern Presidents and Congress (until, of course, President Obama attempted to further enlarge the range of actions available to the Executive). Once Congress became a full-time legislature (a development bought about by the invention of the air conditioner), recesses were for fairly short periods of time and the Senate started holding pro-forma sessions was specifically to prevent the President from making a recess appointment during an intra-session recess.

Scalia’s point of view reflects Alexander Hamilton’s interpretation of the Recess Appointment Clause, which is found in Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution. In Federalist 67, Hamilton argued:

The ordinary power of appointment is confined to the President and Senate jointly, and can therefore only be exercised during the session of the Senate; but as it would have been improper to oblige this body to be continually in session for the appointment of officers and as vacancies might happen in their recess, which it might be necessary for the public service to fill without delay.

In the early years of the government under the Constitution, it was not unusual for Congress to only meet for two or three months out of the year, meaning vacancies might indeed be seriously delayed if not for the exercise of the recess appointment power.

Since the majority interpreted the term “recess” broadly and found that the President could appoint to any position during any recess, it raises the question of whether the President could invoke it anytime including, for example, during a “half-hour siesta” (Scalia, 13). However, this would be absurd, since the Framers wanted to limit the arbitrary use of government power, especially by the Executive. So the majority was forced, practically speaking, to rule on how long the Senate must be out of session for the President to deploy his power. They could say with confidence that a break of three days would be absolutely impermissible. The Constitution requires one Chamber to secure the other’s permission to adjourn for more than three days, so they reasoned that a recess for that time or less “is not a significant interruption of legislative business” (20). Further, in surveying the history of intra-session recess appointments, they could not point out any that were made during breaks lasting less than 10 days. “The lack of examples suggests that the recess-appointment power is not needed in that context” (20). However, they note that appointments made during a four- to nine-day recess would only be “presumptively” invalid, since they anticipate “that some very unusual experience” might make such an appointment permissible.

In this case, the period during which the Senate was not actively conducting business lasted for longer than 10 days. However, Noel Canning alleged that the pro forma sessions, held every three days, were legitimate sessions, meaning a 10-day recess did not occur; the Administration disputed this. The majority determined “that when the Senate declares that it is in session and possesses the capacity under its own rules, to conduct business, it is in session for the purposes of the Clause” (36). Obviously, the Senate was declaring itself in session. Further, the majority agreed that the body could conduct business if it desired, for instance, via unanimous consent. Since the Senate retained the “capacity…to conduct business” even if it did not exercise its powers and the pro forma sessions were being held every three days, President Obama’s recess appointments in this case were ruled unconstitutional.

The majority’s holding that the pro forma sessions were genuine sessions were the most important way that they upheld legislative prerogatives. Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution provides, “Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings”, and, as Justice Breyer noted, the “Court’s precedents reflect the breadth of the power constitutionally delegated to the Senate” (35). In other words, the Court should generally—but not necessarily—defer to the Chambers when ruling on their internal affairs, which includes determining when it is in session.

The deference to Congress in its internal affairs is crucial to a healthy democracy. Legislative procedure is an integral part of how our laws are created, and Members of Congress use them as tools in the act of representing their constituents. If the President or the judiciary were to ignore or write-off Congress’ constitutional requirement to create their own rules of operation under Article I, Section 5, the Members’ individual and collective influence would be diminished and the Executive’s power enhanced. One way of preventing such a situation is for the Court to consistently and emphatically rule that the Chambers of Congress are supreme in their own internal affairs.

Another important aspect of the majority’s decision is that it squarely says that the recess appointment power is not a tool for circumventing opposition in the Senate. Towards the end of the opinion, the majority writes, “the Recess Appointments Clause is not designed to overcome serious institutional friction”—a rather polite way of saying gridlock. Likewise, when it writes that a recess would generally have to be at least 10 days for a President to use his power, unless some calamity necessitates a more immediate appointment, the majority notes, “It should go without saying…that political opposition in the Senate would not qualify as an unusual circumstance.” The refusal of Members of Congress to acquiesce to either the President’s or their colleagues’ agendas is a legitimate feature of America’s Federal system.

But what the Supreme Court gives with one hand, it takes with another. Although the majority does not consider congressional gridlock an extraordinary circumstance permitting a recess appointment during a break lasting fewer than 10 days, in effect, it still allows the President to circumvent the Senate via recess appointments. The majority determined that the President could use his recess appointment power to fill vacancies that existed before the beginning of a recess. Thus, in the face of senatorial opposition, he could simply wait until the Chamber is in recess, and fill up whatever position needed filling—that is, of course, if the Congress ever takes recesses in the future. Since the pro forma sessions are genuine sessions, they can still be used to block Presidential appointments. So, practically speaking, for the Senate’s day-to-day business, that status quo that existed before President Obama’s attempted “recess” appointments has been restored. However, instead of having to meet in pro forma sessions every three days, the Senate will have to meet every nine days to prevent a recess appointment. This also means that the positions that open before a recess will either remain unfilled, or be filled with acting officers.

The fact that the President will still have to endure vacancies and rely upon acting officers until he nominates functionaries pleasing to the Senate is ironic, since the Supreme Court majority intentionally interpreted the Recess Appointments Clause to ensure that the President would have significant leeway in filling positions. Today, the party opposing the President routinely tries to block nominees, whether they are the Senate majority or minority. When the Senate majority and the President are of opposition parties, the Senate will continue to meet in pro forma sessions. Even when the Senate majority and the President are of the same party, the minority is still able to halt nominees, despite the abolition of the filibuster for the all appointments except those to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court majority alleged that Justice Scalia’s interpretation of the Recess Appointments Clause “would basically read it out of the Constitution” (40). In effect, however, with the way nominations are handled today, the majority’s interpretation does not strengthen the Clause either.

Although the Noel Canning decision did not strengthen the President’s hand today, the future might be a different story. The Constitution contains a little remarked provision:

[The President] may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, and in Case of Disagreement between them, with Respect to the Time of Adjournment, he may adjourn them to such Time as he shall think proper…(Art II, Section 3)

As Justice Scalia presciently points out in his concurrence, going forward, what is to stop the President from invoking this power to force a recess long enough to trigger validate his use of the recess appointments power? The Supreme Court majority’s opinion makes it a viable option for the President, whereas the concurring justices’ opinion that the vacancy must come about during a recess forestalls this possibility. One can object that it has not been tried before, and that an abuse of power like that would never be attempted. In the long annals of political history, however, far more egregious abuses of power have occurred. Rectitude of character is not a constitutional qualification for the Presidency. As Justice Scalia notes, “the Constitution does not entrust the Senate’s role in the appointments process to the vagaries of character and politics” (29). We can only pray that America will not elect a President who would succumb to the temptation to engage in such constitutional chicanery.

Even if the Court had interpreted the Recess Appointments Clause more narrowly, as we would have wished, they would not have settled the underlying issues that gave rise to this conflict. This incident was decidedly political, the culmination of the tit-for-tat the parties have engaged in on the subject of nominations for the past couple decades. Resolving these issues is beyond the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction. That, thankfully, is a decision the voters have to make.

For other posts we have written on recess appointments, see:

Obama Appeals Recess Appointment Ruling to the Supreme Court

And for all our posts: Congressional Institute Blog Archive